When I first considered therapy, I searched an online directory and combed through bios searching for my ideal therapist, who was nothing but a hazy reflection of myself: an Indian therapist. An Indian American female therapist, to be clear.

Instead, should I have searched for a biracial therapist or a multiracial or mixed race counselor?

I’m biracial—Indian and White—but my way of navigating the world is largely shaped by my Indian mother.

Does race matter when choosing a therapist? More on this below.

Would a biracial therapist or Indian therapist understand me best?

I’m biracial—Indian and White—and even though I'm multiracial my way of navigating the world is largely shaped by my Indian mother.

I lacked the energy to explain my mishmash culture to a new person.

My mother quit her PhD program and then her job to stay with my brother and me until we left home for college.

To this day, I struggle to navigate the expectations of an Indian mother and a White father simultaneously.

This wasn’t, however, my primary reason for pursuing therapy.

My heart was in a fickle place—caught between longing and utter apathy.

During the COVID-19 global pandemic, I left North Africa, where I’d been teaching English, to return home to a situation that was much more severe.

To this day, I struggle to navigate the expectations of an Indian mother and a White father simultaneously.

Viable jobs were vanishing, uncertainty and collective “COVID trauma” were creeping into every facet of social life, and I was a listless twentysomething with a general lack of direction.

But mostly, it was the gentle onset of a slow and crippling depression, a lack of anticipation, and a certain numbness that made each day blur into the rest.

Most therapists in the United States are White, according to the U.S. Census Bureau's American Community Survey, although a recent American Psychological Association (APA) data point study suggests that the field is slowly diversifying.

After searching, I settled on a therapist: a young mother by the name of Preeti*, in whom I was ready to confide all the colorless days and paranoid thoughts.

And, while I didn’t assume direct continuity between my emotional-mental state and my cultural background, I suppose I expected the two to mutually speak to one another, in that each is a significant though not comprehensive lens into my psyche.

How does race affect therapy?

Research is mixed about whether the most successful therapeutic relationships are those between a client and therapist of the same race.

Though almost all clients—and clients from “minority” backgrounds in particular—have reported in surveys and studies that they felt more comfortable and better able to communicate with therapists of the same race, it’s not clear that their relationships are actually more productive or beneficial than others.

Research is mixed on whether the most successful therapeutic relationships are between a client and therapist of the same race.

Many Black Americans have expressed reasons why they prefer to see a Black therapist.

Similarly, many Asian Americans and AAPI individuals have expressed that they prefer to see an Asian therapist or a therapist who shares their own racial and cultural background.

How someone who is biracial defines racial identity

During our first few therapy sessions, Preeti gathered background information, and we discussed day-to-day tribulations, roadblocks, recurring negative thoughts.

Then, one day, I mentioned the confusion I sometimes feel when negotiating my racial identity.

She asked me to make an “identity pie chart.”

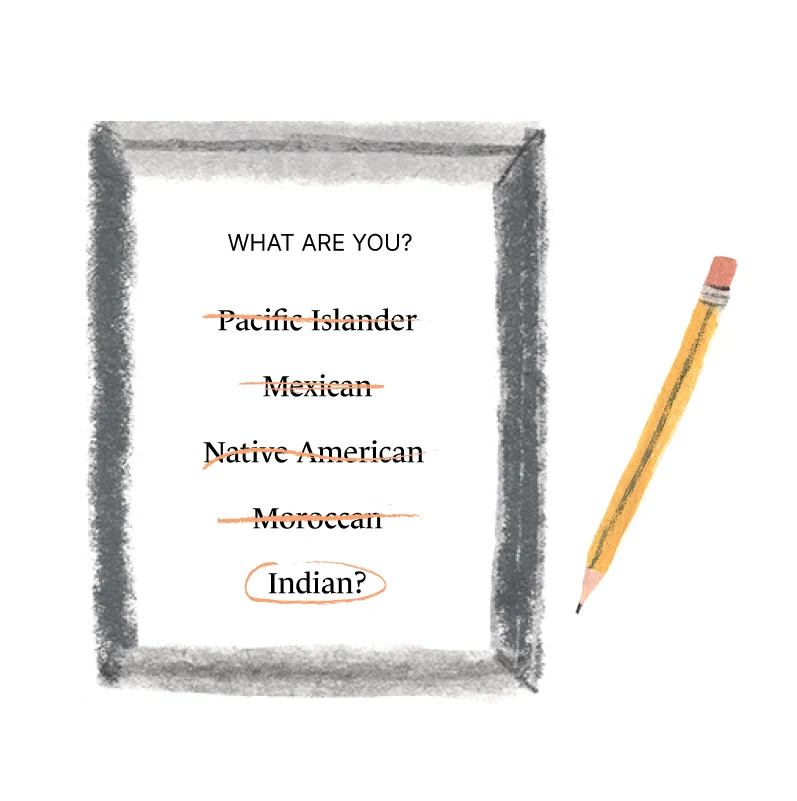

In my mind, the exercise was akin to the ubiquitous “What are you?” question.

Though usually lobbed in good faith, it tends to send me spiraling.

While I’m often confused on account of my Whiteness and Indian-ness, I rarely feel oppressed.

Deflecting, I told her I was a racial grifter—that in elementary school, I shaded in “Pacific Islander” on standardized tests because I wanted to live in the setting of The Island of the Blue Dolphins, my favorite book at the time.

I told her that in my hometown in Texas, most people assumed I was Mexican.

Whereas, when I worked in Montana, perfect strangers would ask me if I was Native American.

In India, on the other hand, I rarely pass as Indian.

In Morocco, life was easier when I blended in as a local, which I usually could. Though men I encountered in taxis and at train stations would mock me, at times, for my broken Darija.

“Are you really not Moroccan?” they would ask. “Then, what are you?”

Out of breath, I told my therapist that without effort, I can pass in all of these ways because of my racial ambiguity.

It has made me feel unmoored and dishonest sometimes, I told her, but it's also made me feel powerful.

In a world of perfect strangers, I alone hold the power to divulge who I am.

Despite the unpredictability of others’ perceptions of my race, my conversation with Preeti quickly spun into absolutes.

She used all the terms and buzzwords: privilege and systemic racism to explain the macro-picture structures of society; neocolonialism and inherited trauma to push against my hesitancy to consider myself oppressed in a sustained or structural way.

“I want you to think of oppression less as a competition and more as a spectrum,” she told me, after I voiced my disillusion with the label “person of color” (POC).

It recenters Whiteness, I feel, because it collapses non-White identities into a blanket group, as if we all share common interests and agendas—wishful if not entirely incorrect.

It feels soul-crushing to interpret my day-to-day emotions through the lens of color.

So, while I’m often confused on account of my Whiteness and Indian-ness, I rarely feel oppressed.

“Which is not to say that systems of oppression don’t exist,” I tried to clarify.

Preeti smiled and reminded me, again, that it’s a spectrum.

I was familiar with these terms—they structured social life at my small liberal arts college—and had felt, for a long time, that these labels often fall short.

Despite the small hope I hold for the political possibilities of a term like “people of color” and its acronym POC (solidarity, maybe, or unification) and my continued observations of the realities of privilege and systemic racism, it feels soul-crushing to interpret my day-to-day emotions and outcomes primarily through the lens of color.

By the end of our session, I was at a loss for words.

My therapist reminded me about the assignment to create the pie chart—to identify and slice those pieces of my identity that I deem inseparable from one another.

After we hung up, I sulked for the next hour. It was the first time that my therapist and I had veered into the cerebral, impersonal territory of identity politics.

Why did it bother me that she had attributed various circumstances in my life to large-scale phenomena I believe to be true?

I wasn’t bothered by her use of terms like anxiety and depression, near-universal experiences that plague humans the world over.

While writing this piece, I realized that I had confused racial identity for what some psychologists called racial worldview.

According to a 2013 article in the American Journal of Community Psychology, racial worldview match might be even more important than racial identity match.

Though therapy clients often assume shared commonalities based on culture, racial match might not even be a significant predictor of therapy outcomes.

It’s this distinction—between how I perceive race and how I am perceived because of my race—that has come to the forefront in my journey through therapy.

How therapy has helped

I benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), in part, because reflecting my ideas and desires with another person can be a great boon for my mental health and clarity.

Part of the allure of therapy—for me at least—is that it’s a space in which you, the individual, are treated as such: a complex person with unpredictable life circumstances and moods.

Discussing my problems as symptomatic of a broken system, rather—abstract and untethered from the specificities of my experience—left me feeling disempowered, ultimately. It felt like there was little in my power to find peace with my multivalent identities.

Even though these “racial worldview” held water for me in theory, they felt trite and tired when trying to shove my life into their cookie-cutter confines.

Despite my hesitation, I drew the pie chart.

Staking my pen in the circle’s center and moving outwards, I felt the inarticulable weight of each of its parts. “Indian” and “brown” were separate though similarly-sized slices in my pie, while “vague American-ness” and “shy” were other separate pieces.

I still see Preeti, though we largely do not talk about race anymore. It comes up, of course, in the way that it inevitably does occasionally.

I’m not sure how I might depict my identity now, were Preeti to ask me to complete the exercise again. But perhaps uncertainty is baked into the premise.

For a little less than half of the circle I left blank, and inside of it I drew a single question mark. That section of the pie is a testament to my capacity for change, I thought, or something that might avail itself with time.

Finding the right mental health therapist—someone who’s a match for your specific needs and personality—may be the best decision you ever make.

How to find the right therapist for you

Here’s how to make it easier to find the right person to help you.

Start by going to the Monarch Directory by SimplePractice at meetmonarch.com. The directory can help you find a therapist aligned with your specific needs and goals.

Choose to view therapists by specialty (including therapists near you who specialize in multicultural concerns).

You can search for areas of specialty such as anxiety, PTSD, depression, or grief.

For example, you can quickly find all the therapists in New York City who specialize in anxiety or all the therapists in Oakland who specialize in depression.

Additionally, find therapists who accept your health insurance plan or therapists offering telehealth video appointments and 15-minute free initial consultations.

* name has been changed

READ NEXT: How Do I Know What Kind of Therapist Is Right for Me?

Need to find a therapist near you? Check out the Monarch Directory by SimplePractice to find mental health therapists with availability and online booking.

Atkinson, D. R., & Lowe, S. M. (1995). The role of ethnicity, cultural knowledge, and conventional techniques in counseling and psychotherapy. In J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casas.

Herman S. M. (1997). The relationship between therapist-client modality similarity and psychotherapy outcome. The Journal of psychotherapy practice and research, 7(1), 56–64. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3330484/

Lin, L., Stamm, K., & Christidis, P. (2018). How diverse is the psychology workforce? American Psychological Association (APA). Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2018/02/datapoint

Meyer, O. L., & Zane, N. (2013). The influence of race and ethnicity in clients' experiences of mental health treatment. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(7), 884–901. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21580

Pappas, S. (2019). New guidance on race and ethnicity for psychologists. American Psychological Association (APA). Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/12/ce-corner-race

Suzuki, L. A. & C. M. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (p. 387–414). Sage Publications, Inc.