When I was growing up, my South Asian household treated therapy with about the same respect as fortune telling.

To my Indian immigrant parents, counseling and mental health support was a luxury Americans flippantly wasted money on—in the same vein as indulgent spa treatments and personal fitness trainers.

As a teen, I didn’t know anyone who regularly saw a therapist.

When I was growing up, my South Asian household treated therapy with about the same respect as fortune telling.

Consequently, my understanding of how psychotherapy actually works was limited to what I saw in movies: couples bickering in front of a bespectacled marriage counselor.

As I grew up and went to college, I discovered that my Indian-born parents' mistrust of therapy and mental health stigma did not seem to be shared by my peers whose parents who had grown up in America.

Many of my non-immigrant peers had grown up viewing therapy as an occasionally necessary tool for self-improvement.

So, what made my family different?

How do South Asians view mental health?

Indian culture prioritizes studying hard and working harder, which can often lead to the reduction of personal problems to “distractions'' which are brushed aside.

On top of this, a lack of access to mental health services has led to damaging effects in India and among South Asians living across the globe.

A 2017 study found that 197 million people live with mental disorders in India, including 46 million with depressive disorders and 45 million with anxiety disorders.

This unyielding pressure to catapult one’s family into a higher class takes its toll on the psyche.

Among those Indians not born into wealth (which, in a country with a population of 1.5 billion, is most people), many children bear the heavy burden of being their parents hope of ending generations of economic poverty for the family.

Consequently, for South Asians there is a great deal of weight placed on studying and working hard as potential paths to financial success.

This unyielding pressure to catapult one’s family into a higher class takes its toll on the psyche and on our mental health.

And though South Asian families emigrating to Western countries are often viewed as successful, it still doesn’t dissolve the cycle of intense parental pressure.

Indian American immigrants who grew up feeling the onus to bring their families out of poverty often impose similar expectations on their own children, who then feel the pressure to maintain the upward trajectory their parents achieved and to establish a lasting legacy of success.

Success, in this case, is measured by a high salary and a well-timed, suitable marriage.

Issues like sexual assault, substance abuse, marital problems, or mental illness are “imperfections,” and contribute to eroding the standing of a family.

Failure is measured not only by the absence of these markers, but by any perceived defect—even those out of one’s control.

Issues like sexual assault, substance abuse, marital problems, or mental illness are “imperfections,” and contribute to eroding the standing of a family.

Indian culture radiates supreme joy, innovation, and vibrant colors, but in the shadows of all this luminescence lurks a tradition of shame.

Acknowledging pain or “failure” is treated as anathema to the resilience of South Asian culture, and so that pain is often ignored altogether.

When internalized, this stigma only amplifies pain and shame.

Indian women's mental health crisis

The South Asian stigma around mental health conversations and the ensuing culture of shame has led to devastating effects in India.

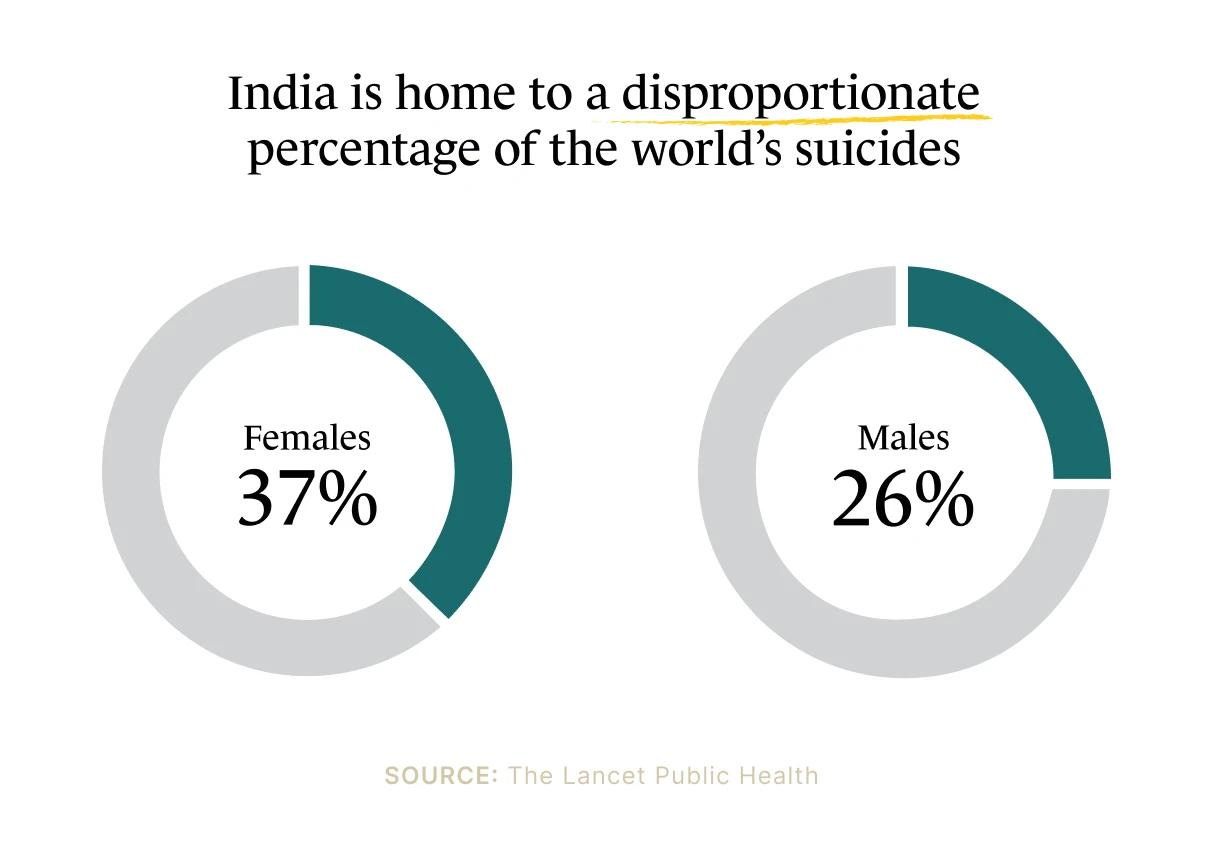

In 2016, an alarming report claimed that India made up 36% of all suicides reported globally for women that year.

In an interview with NPR, one author of the study, Dr. Lakshmi Vijaykumar, a psychiatrist with 25 years of experience in suicide prevention strategies, spoke about the mental health crisis in India.

She references a 2014 World Health Organization study that found Asian women had the highest suicide rates in the world, reporting that 60% of all women who died by suicide in 2014 were from India and China.

Vijaykumar emphasizes how suicide has yet to be decriminalized in Indian law: The Indian Penal Code (IPC 309) still levies punishment for attempted suicide.

This contributes to the stigmatization of suicide, consequentially contributing to more South Asians dying by suicide.

Breaking the South Asian taboo around therapy

Bearing witness to members of the South Asian American community whose mental health has suffered—due to both the pressure to be a golden child and the compounding shame around that suffering—left me not wanting to be a statistic.

As I set out on my own, I made friends who shared how therapy was and continues to be crucial in helping them understand their relationships and behavior.

Others said therapy had helped them dissect and heal from trauma.

They showed me that vulnerability and a willingness to examine your demons is an expression of strength.

Acknowledging pain or “failure” is treated as anathema to the resilience of South Asian culture, and so that pain is often ignored altogether.

I'd been trained from a young age to hide unpleasant emotions, which, of course, meant they just bubbled under the surface.

I had spent my life avoiding and burying so many memories and feelings I didn’t want to confront. I wanted the chance to address and unpack them with a therapist.

And if deciding to care for my mental health served as further rebellion against cultural norms, so be it.

But it wasn’t that easy.

The closest I had ever gotten to therapy in my twenties was weekly doses watching Oprah's Super Soul Sunday.

My enthusiasm for starting therapy withered when I discovered the the cost of therapy put it out of reach for me.

And so, I placed my mental health on the backburner until I could find a way to afford counseling. It would turn into years of waiting.

At 30, I quit my non-profit job and began the exciting yet financially unstable pursuit of a career in comedy.

On Medicaid for the first time in my life, I was astonished to discover that my new health insurance offered therapy at select locations with zero copay.

Ironically, it only took having a distressingly low monthly income and needing government assistance to afford therapy!

I had spent my life avoiding and burying so many memories and feelings I didn’t want to confront.

It couldn’t have come at a better time. As I gained traction in the comedy scene, I began to perform almost every night of the week.

With the increasing success came mounting feelings of anxiety leading up to, during, and/or after a performance.

I hoped therapy would assist in addressing my anxiety before it was debilitating.

But now, a year into biweekly sessions with my therapist, I've been shocked at the breadth of the discoveries and healing my sessions have provided me.

In one meeting, I casually brought up a romantic relationship from a decade ago that I was sure I had moved on from.

Minutes later, I found myself crying while recounting specific details.

I discovered I had unconsciously buried that experience out of habit, never addressing its profound impact on my psyche and heart.

I placed my mental health on the backburner until I could afford the luxury. It would turn into years of waiting.

I still often start speaking to my therapist about a specific topic totally composed and collected, only to have a stream of tears reveal the depth of something I thought I had already figured out and self-treated.

Having a therapist validate my pain and work with me to examine key events impacting my life has provided me with newfound strength.

I’ve still never spoken to my Indian American immigrant parents about being in therapy.

Maybe I’m still avoiding the hard conversations around a mental health stigma that is alive and breathing.

Saving face by any means necessary is still a stain on an Indian culture that preaches family values.

Until the stigma around mental health is widely dismantled in South Asian culture, feelings of shame, hopelessness, and isolation will lead to reluctance in asking for help or seeking treatment, undoubtedly resulting in more suffering.

I feel lucky and grateful to have been initiated into the unofficial club of therapy enthusiasts and hope to see steps towards improved access, awareness, and acceptance regarding mental health in the Indian community.

Pursuing treatment for mental health concerns can be the best method to stop the bleeding.

Pain can live on the surface, be buried in our subconscious, or habitually ignored altogether.

It is an act of strength, courage, and love to enter the dark caves where our pain lives and is well worth the long voyage towards the light.

How to find a South Asian therapist for mental health support

The Monarch Directory by SimplePractice makes it easy to find a therapist near you who is accepting new clients.

Choose to view therapists by specialty (including therapists near you who specialize in multicultural concerns).

Additionally, find therapists who accept your health insurance plan or therapists offering telehealth video appointments and 15-minute free initial consultations.

On Monarch, you can view therapists’ availability and request an appointment online, often without ever having to pick up the phone.

If you want to find a therapist that specializes in multicultural concerns or offers a multicultural treatment approach you can enter your location and filter “By Specialty” and “Approach” to narrow down your selections from there.

READ NEXT: Should a Biracial South Asian Woman See an Indian Therapist?

Need to find a therapist near you? Check out the Monarch Directory by SimplePractice to find licensed mental health therapists with availability and online booking.

Dandona, R., Kumar, G. A., Dhaliwal, R. S., Naghavi, M., Vos, T., Shukla, D. K., … Khanna, T. (2018). Gender differentials and state variations in suicide deaths in India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. The Lancet Public Health, 3(10), e478–e489. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(18)30138-5

Sagar, R., Dandona, R., Gururaj, G., Dhaliwal, R. S., Singh, A., Ferrari, A., et al. (2020). The burden of mental disorders across the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(2), 148–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(19)30475-4